Starting from the Beginning: Period English Vocal Music Suitable for SCA Performance

(This article was written for the “To Be Period” summer issue of The Northern Watch, Endewearde’s Baronial

Newsletter. There is a playlist of music with which to follow along: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL_AGpqxzmAWpYDVGG31Y_OhX9PbPdHzXq.)

As a singer, often I am asked about singing and music in the Society. “Where should I begin?” is the question, often followed by, “How do I start?”

Excellent questions both! If one searches for “SCA songs” or suchlike on the internet, the responses are dizzying in size and of extreme variance in quality. If one wanders the campfires of an event or sits at a “bardic circle” often music is performed which is certainly out of period but with which many identify and find entertaining. Filk songs like “A Grazing Mace” make us laugh (or cringe) together, and music of the modern middle ages relates to us in our own tongues with music that’s familiar to our ears, moving us with the stories and emotions we’ve likely experienced ourselves. Also popular are ballads of many ages, from the Child Ballad collection to folk songs of surprisingly modern origin, and the occasional piece which is unabashedly so.

But my answer would be, were I answering truly, “You should begin somewhere between the beginning and the end.” What I mean by that is “the beginning and end of the Middle Ages and Renaissance” – the period we strive to recreate in the SCA.

It is somewhat ironic that as a group of people who embrace history, arts, clothing, martial styling of the Middle Ages and Renaissance seem reluctant to embrace the music of our medieval ancestors. It may be because we, as modern people, perceive medieval music as inaccessible or complicated, as too dull or too challenging, as unappealing to our ears, minds, and hearts.

I prefer to think that it’s more because we don’t know where to begin. So let’s begin with what we mean by “period pieces” and go from there. We’ll travel backwards through English music that can be learned with relative ease by a modern person who has an interest in doing so. To aid in the exploration of the pieces in this article, a YouTube channel has been created which includes nearly all the songs mentioned in this article. It can be found at https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL_AGpqxzmAWpYDVGG31Y_OhX9PbPdHzXq.

“Period” pieces have music and lyrics written prior to 1599 and can be documented as such. Sometimes a period lyric would have its own composition or score, and sometimes it would be matched with a well-known period tune. The latter was such a common period practice that some printed broadsides would simply say the lyric ought be sung to, “some pleasant tune” and let the singer choose what that might be. We refer to that style of putting a lyric to a separate tune “contrafact.” (It is the great ancestor of filk.)

Within the SCA, contrafact pieces are generally as described – they are period tunes with lyrics added (or altered). Sometimes the lyrics are entirely new and set to a period song, a bit of medieval lyric set to a dance tune or period song. The Eastern anthems “Ave Tigris“ is set to an anonymously composed 13th century tune,and “Carmen Orientalis” has a melody borrowed from “In Taberna” from the 13th century Carmina Burana. Both are examples of contrafact, as would be any little thing you sing to the tune of the “Maltese Bransle.” (You can sing a wide variety of things to the tune of the Maltese, including “A Grazing Mace.”)

But with a timeframe that stretches from 1599 through antiquity, where does one begin to find pieces which are period and accessible? And what about John Dowland, John Playford, and Thomas Ravenscroft – all popular English composers and collectors whose music was published post-period? Sticklers to a vision of a pre-17th century Society may find these pieces to be not their cup of ale, but I find that the music that falls at the modern edge of the SCA period to be quite accessible and it has a familiar feel to it that some earlier music may not, making it a good place to begin a journey toward earlier music. These fall, in my view, as “honorary period” music. And since this is a time when music is finally being published on a more broad scale, and we have many books of collected works with notation that’s much like what our modern eyes are used to as well.

Dance tunes provide a wealth of options. “The English Dancing Master” was published in 1651 by John Playford. It includes numerous songs which are popular dancing songs, several of which also have lyrics traditionally attached to them: The tune “Goddesses” is used for both “The North Country Lass up to London did Pass“ and also for the setting of Shakespeare’s “Blow Blow Thou Winter Wind” from As You Like It, which was written in 1599. Both of these versions have been heard in Endewearde in recent memory. The beautiful “All in a Garden Green” seems have been, at least in some related form, taken from William Pickering’s “A Ballet intituled All in a garden grene, between two Lovers” as early as 1563 when said song was licensed at the Stationers’ Comp. Register for printing.(1) “Hearts Ease” is attached to a lyric entitled “Misogonus” (c1560) which urges us to “Singe care away with sport & playe, Pasttime is all our pleasure, Yf well we fare, for nought we care, In mearth our constant treasure…”

The common theme of pleasure, revelry, a carefree life, and often love in its sorrow joy, are utterly appropriate sentiments for life in the Society.

Thomas Ravenscroft (c.1592 – 1635) published five books between 1609 and 1621, but was a collector as much as a composer. Much of his music is viewed as “plausibly period” including “Three Blind Mice” – which was a round at the time of its first publication but one in an eerie minor key which discussed the preparation of tripe for a meal, in addition to mice. The Ravenscroft song “Three Ravens” is a common on in the SCA. The songs in the collection include part songs and rounds about drinking, politics, common life, street cries, love, and religion.

Some music thematically could be on the radio now – “Sellinger’s Round” was published in 1609 by William Byrd (1539-1623). We have for it several sets of lyrics, notably the “Country Man’s Delight” brightly sings, “Oh, how they did jerk it. Caper and ferk it, Under the greenwood tree.” As usual there is another version of the lyric with a quite different theme: “Farewell Adeiu” talks of banners and battles and knights, written by John Pickering in 1567.

Byrd was a noted student of Thomas Tallis (1505-1585) who is regarded as a master of the choral voice and whose focus was religious works. The famed “Tallis Canon” has had many lyrics appended thought the most well-known is “Glory to Thee My God This Night.” It is a good representative of Tallis’ sound. While usually secular music is performed in the Society, it is important to note that faith was very much required by people and religious services were not missed without grave reason.

Thomas Morley (1557-1602) was a student of Byrd, and and also a prolific composer. He wrote sacred music, but also a great deal of secular music, many are love songs but others are simply silly. One piece, “Will You Buy a Fine Dog” begins with the lyric “Will you buy a fine dog, with a hole in his head?” and continues with a nonsense chorus which might cause one to titter a bit between the verses.

John Dowland, a contemporary of Morely, is beloved through the ages. He worked in many of the courts of Europe, and was even rumored to be a spy for the English Queen. In 1597, Dowland published his First Book of Songs. Among the pieces in that work is “Come Again Sweet Love” – a piece which is well-known and relate-able – passionate desire for a tempestuous beloved. “Her Eyes of fire, her heart of flint is made, Whom tears nor truth may once invade.” Dowland’s work has had a lasting appeal; Sting released an album of Dowland’s songs in 2006.

Printed broadsides begin to appear in about 1550 for purchase which opens up the world for the collections of Ravenscroft, Byrd, and others. While musical treatises and other books, most notably versions of the Bible, are printed by Gutenberg’s press after its invention in 1439, much of the music before that was captured as it had been for centuries – by pen and ink, and required literacy (or an excellent memory) to learn.

As we move backward toward the origin of written English song we still have a wealth of lyric – over two thousand pieces written in Middle English – but far fewer lyrics are paired with written notation. However, those for which we have both are fascinating and moving.

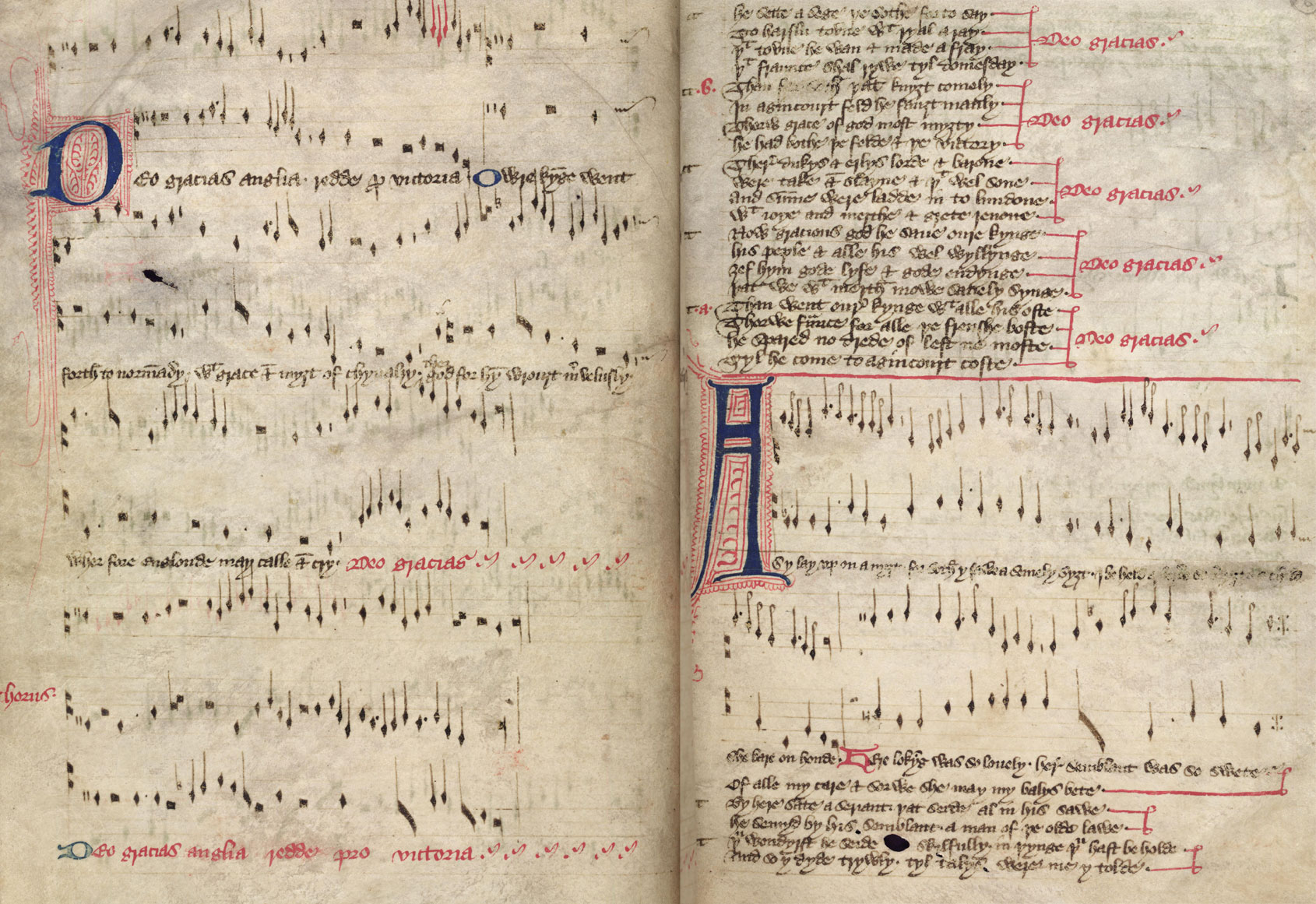

“The Agincourt Carol” was composted in 1415, and tells the tale of the famed battle of King Henry V, “Owre kynge went forth to Normandy, With grace and myght of chyvalry; Ther God for hym wrought mervlusly, Wherfore Englonde may calle and cry, Deo gratias, Deo gratias anglia, redde pro victoria.” It is stern but beautiful and the three-voiced chorus is haunting. It is one of the few highly nationalistic songs of the period – written of war, battle, history, and nationality rather than of love or religion.

One of the most beautiful love songs in English is “Bryd One Brere.” Written on the back of a papal bull in the 1300s, it is a soaring and sweet song, “Bryd one brere, brid, brid one brere, Kynd is come of love, love to crave, Blythful biryd, on me thu rewe, Or greyth, lef, greith thu me my grave.” Many songs of love spoke of the beloved in terms of nature and separation from the loved one was like death. Similar themes are found in religious music of the time, but with Mary, Christ, or God as the subject of the love.

“Merie it is” is another secular love song from the same period. It speaks to our hearts from the 13th century of how happy life is when it is in its ‘summer’ of love and how sad and sorrowful it is when the love has grown cold or ended in its ‘winter.’ The tune dances and lilts, it is both simple and distant. The Middle English words, while different from our modern tongue, are still quite easy to understand and sing.

Of course this brings us at last to what is likely the best-known piece of medieval English music – “Sumer is Icumin In.” Believed to have been written in the mid 13th century in an abbey, it has been assumed that the piece was lost in time from the 14th century to the 19th, when its rediscovery made it the popular piece is is today. It sings of the fertility of summer and all the things which happen, from the singing birds to the leaping, and even farting, animals are celebrated in song. “Well singeth the coo-coo” in this round, found in only one manuscript, it is paired with a Latin text “Percipce Chrisicola” making it the earliest known text to combine the sacred and secular pieces into a single document. It’s an excellent reminder of the dual nature of medieval life in which the sacred and the secular were utterly intertwined.

As you explore the richness of music in the SCA period you may find that it is more pleasing and entertaining than you may have thought. The themes range from silly to somber and there are songs within the SCA time period which are appropriate for all occasions. When these pieces are performed it brings us closer to our past and enriches and deepens our connections to the times which inspire us.

The performance of medieval music in the Society tends to do more than merely entertain – it is a magical transportation device which seems to subtly alter our realities. I like to think it helps us not only better know about the people we honor in our recreation of an earlier time, but also bring their lives closer to our own.

Resources:

All the pieces in bold may be heard at: http://tinyurl.com/NorthernWatchMusic

http://www1.cpdl.org/wiki/index.php/Will_you_buy_a_fine_dog%3F_%28Thomas_Morley%29

http://www1.cpdl.org/wiki/index.php/There_were_Three_Ravens_%28Thomas_Ravenscroft%29

http://www1.cpdl.org/wiki/index.php/Three_Blinde_Mice_%28Thomas_Ravenscroft%29

Byrd one Brere – http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/medlyric/brere.php

Merie it is – http://www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/dept/scwmss/wmss/online/medieval/rawlinson/images/G0223650.jpg

Agincourt Carol manuscript – http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/medlyric/agincourtms.jpg

Sumer – http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/musicmanu/sumer/

Note 1.The Roxburghe ballads, Volume 8, By William Chappell, Ballad Society;

This article first appeared in “The Northern Watch”, Barony of Endewearde’s newsletter. (http://www.northernwatch.net/uploads/1/1/1/8/11184890/2013_summer_northern_watch_b.pdf)